The Common Egg-Eater (Dasypeltis scabra)

Dasypeltis scabra by Animal Reader

Taking a trip down memory lane is always a gamble. We've all had good and bad experiences but I think it's fair to say that both help shape us into who we are today.

A while ago whilst visiting my mother-in-law, I started to truly appreciate the impressive bookshelf that my husband cultivated as a child. Reading has always been one of his favourite things to do. His bedroom's bookshelf (the one he had as a child) is filled with fantasy books. Next to these books is a picture of his child-self smiling whilst pointing at the spider climbing his naked torso. To this date, he still loves spiders and other critters, which brings me to my biggest find on the bookshelf - a book called 'Amazing Snakes' written by Alexandra Parsons which is part of the 'Amazing Worlds' series published in 1990. As I understand it, this was a birthday present he got alongside the 'Amazing Spiders' book of the same series that was nowhere to be found.

The 'Amazing Snakes' book looked rather worn (which is a good sign if you ask me!). Judging by the wear and tear marks on the book, the most popular section was the two-page feature on the Egg-Eater. It seems that as a child, he was fascinated by their uniqueness and what he described as seemingly 'non-threatening' nature due to their lack of teeth (well, lack of teeth as we see it).

Although the book did not specify which of the two genera of egg eating snakes it was referring to, I believe they 'lumped' Dasypeltis and Elachistodon together. For the purposes of this post, I will be focusing on the most commonly known species of the Dasypeltis genus - the Common Egg-Eater (Dasypeltis scabra).

About the Common Egg-Eater

This snake can be found in Africa, south of the Sahara Desert. It is no surprise, therefore, that most of its habitat is made up of deserts, scrubs and open woodlands. Adults can reach up to 1.1 metres in length but remain fairly thin with a diameter comparable to a human finger. They are nocturnal and usually lay anything between 6-25 eggs.

Some snakes are known for eating Squamata eggs and have developed incredible adaptations to be able to eat these shell-less eggs. However, none have evolved quite like snakes in the Dasypeltis and Elachistodon genera to be able to eat amniotic eggs (or 'hard-shelled eggs). The entire process is fascinating and one of my favourite topics on reptile evolution. So much so, that in his book, Life in Cold Blood, our beloved Sir David Attenborough gifts us with two pages on the egg-eater and their feeding method.

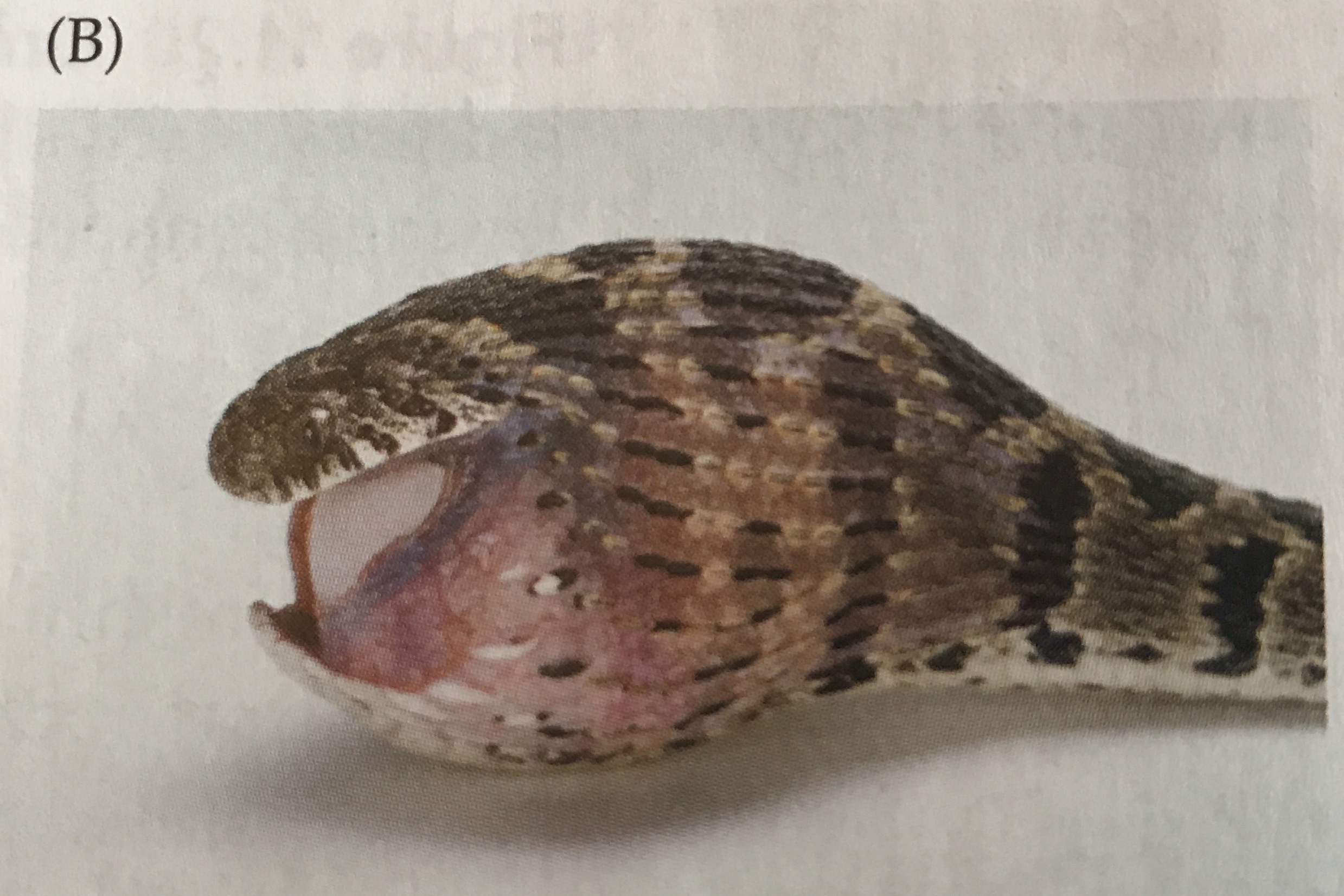

So, how do they feed? You see, despite their small girth, D. scabra can swallow eggs up to four times the diameter of their heads. The small vestiges of their teeth and jaw are covered by a soft mucosal tissue which makes both the 'teeth' and the jaw slide over the egg without breaking it (see images a and b). Once the egg is located behind the snake's throat (see image c), the snake uses its muscles to push the egg through the oesophagus.

Between its 21st and 29th vertebra, the snake's vertebrae are adorned by small down-ward spines (see image d). These spines crack the egg's shell into small pieces as the snake contracts that part of its body. The contraction is such that the snake manages to crack the egg but maintain the egg's membrane mostly intact. This allows the egg's contents to then be passed down to the snake's stomach whilst the cracked egg remains in place. The snake then regurgitates the fragmented eggshell pieces (mostly still connected by the membrane) and continue on its way.

The Pet Trade

Unfortunately, the egg-eater's seemingly non-threatening nature makes it an attractive species for the pet trade. It is often suggested as an alternative to those who may want a 'pet snake' but may not be willing to deal with live or frozen prey.

The reality, however, is that although its bite might not 'hurt', procuring its food source may not be as easy as one might think. For instance, although they can eat prey up to 4 times the diameter of their heads, the vast majority of them, even adults, will feed on eggs that are smaller than a chicken's egg. Juveniles, for instance, will often need to eat eggs that vary in size between a chicken and a quail's egg. As you can imagine, these are not always easy to find. They also tend to eat more frequently then other snake species and it is reported that their excrement can have a rather strong smell - similar to the smell reported by owners that feed their snake on chicks rather than rodents.

References & Sources:

Whilst carrying out research for this post, I came across quite a few published papers on the morphological adaptation found in the egg-eater. One of those papers, for instance, gives a good insight into the potential selective regime that may be conducive to the evolution of the species based on their morphological traits. Therefore, I have detailed below some of the most helpful sources I found and hope that you too enjoy researching this amazing creature!

Attenborough, D. (2008). Life in Cold Blood: A Natural History of Amphibians and Reptiles. BBC Books.

Mattison, C. (2014). Nature Guide: Snakes and Other Reptiles and Amphibians. London, Dorling Kindersley.

Harvey Pough, F. (2016). Herpetology. Fourth Edition. Massachusets, Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Gartner, G.E.A. & Greene, H.W. (2008). Adaptation in the African Egg-Eating Snake: A Comparative Approach to a Classic Study in the Evolutionary Functional Morphology. Journal of Zoology Vol 275, Issue 4:368–374.

Parsons, A. (1990). Amazing Snakes. London, Dorling Kindersley.